(Bilder vom verlorenen Wort) 50 Min Lichtton / optical sound 16mm 1970-74

One day, when I was still a very young girl, I went home from school with Francis Picabia's late son. He informed me about a new invention which he called "television". I liked this idea for quite a while. He, however, continued: "and you can see the singers sing and move their arms." His enthusiasm was quite embarassing and I refused to bother about television any more.

Some years later, I already was a still very young city-boy, I used to dream of picture-poems with rhythm and rhyme, somewhat in the style of Old Brecht.

But I became a musician, and the hot autumn sun of the year 68 found me within the gates of New York City starting to work on a thesis on neutron stars. One morning, however, this girl took me out of town with an old Dodge. And night collapsed above our heads, and suddenly i could see them, for the first time in my life I saw the stars. What a disappointing experience.

The next day I got divorced and left America.

Back in Europe I was looking for something far beyond the decriptional level. I switched to Quantum Field Theory which was nice and not at all linked to any really existing object.

Then, in a moment of deepest despair, I happened to remember "The Old House Passing" which I saw in a moment of irresistable hope.

Right now, as I work as a truck driver I like to think ... I like to think of film as being a long assembly-line on which the filmmaker sits and works, putting information to each single frame that passes his path of existence. Just like these women do it in the factories where they build transistor radios following a planned schedule. Maybe the filmmaker also is the engineer who plans the schedule, but, honestly, I don't really think he is...

***

One year later Werner Herzog asked me to help him shooting some footage in Ireland. This year had been horrible. I was cleaning oiltanks and worked as a computer-programmer. In the evenings I got home from work, went into bars, got drunk and ended in weird situations. Fucking got worse and worse. There were no pictures worth being recorded...

Filmtext:

(Übersetzung des englischen Textes von Vincenz Nola)

Einige Jahre später - inzwischen war ich schon ein noch sehr kleiner Stadtjunge - träumte ich oft von Bildgeschichten mit Rhythmen und Reimen, irgendwie in der Art des alten Brecht.

Aber ich wurde Musiker, und die heiße Herbstsonne des Jahres 68 fand mich in den Toren von New York City, und ich begann eine Doktorarbeit über Neutronensterne. Eines Morgens jedoch nahm mich dieses Mädchen mit einem alten Dodge aus der Stadt, und in Woodstock brach die Nacht über unseren Köpfen zusammen, und

plötzlich konnte ich sie sehen, zum ersten Mal in meinem Leben sah ich - die Sterne. Was für ein enttäuschendes Erlebnis.

Am nächsten Tag ließ ich mich scheiden und verließ Amerika.

Zurück in Europa suchte ich nach etwas jenseits der Beschreibungsmöglichkeiten. Ich wechselte zur Quantenfeldtheorie. Die war hübsch und überhaupt nicht mit irgendwelchen wirklich existierenden Objekten verbunden.

Dann, in einem Moment tiefster Verzweiflung, erinnerte ich mich zufällig an "The Old House Passing", den ich in einer Minute unwiderstehlicher Hoffnung gesehen hatte.

Jetzt, wo ich als Lastwagenfahrer arbeite, denke ich gern ... denke ich gern von Film als einem langen Fließband, an dem der Filmmacher sitzt und arbeitet, an dem er jedes Einzelbild, das den Pfad seiner Existenz kreuzt, mit Informationen füllt, genauso wie es diese Frauen in den Fabriken tun, wo sie Transistorradios bauen und einem geplanten Schema folgen. Vielleicht ist der Filmmacher sogar der Ingenieur, der dieses Schema plant, aber ehrlich gesagt, das glaube ich eigentlich nicht.

Ein Jahr später bat mich Werner Herzog ihm beim Drehen einiger Einstellungen in Irland zu helfen. Dieses Jahr war furchtbar gewesen. Ich reinigte Öltanks und arbeitete als Computer-Programmierer. Abends kam ich von der Arbeit, ging in Bars, betrank mich und endete in üblen Situationen. Das Ficken ging immer schlechter. Es gab keine Bilder, die es wert waren, aufgezeichnet zu werden.

Wyborny's previous film, Birth of a Nation, was organised around a narrative exposition, there is a repetition of the titles and some of the elements of the narrative. This problematic, of the importance of enunciated speech, is thematised in the title of this film, Pictures of the Lost word, the lost word is sought for in a series of images, accompanied by a few short, possibly autobiographical statements.

The image band presents a series of static views of a small number of rural and urban scenes (the prominence of Battersea power station probably a cinematic reference (LeGrice) with a few people present. Each scene is presented several times in succession, each time by a lens of different focal length, such that the impression is both of repetition (shots of the same 'content') and difference (different focal length). As the film progresses the shots become shorter and of a more exotic locale, as Wyborny follows Werner Herzog to Ireland and Morocco, and with increased emphasis on the processed image using colour negative similarly to Birth of a Nation but even more aestheticised. The film evokes an overwhelming impression of nostalgia, reinforced by its use of music (reminiscent of Satie) the flow of which is, however, constantly interrupted creating uncertainty as to its interpretation. - Mark Nash.

‘Wyborny trained as a mathematician, worked as a cameraman on Werner Herzog's Kasper Hauser. He first attracted the attention of the New York and London avant-gardes five years ago for his elliptical narratives, Dallas Texas - After The Gold rush (1971) and The Birth of a Nation (1973). Their plots, 'collapsed' by the optical transformation and repetition of individual shots, move from anecdotal narrative to an examination of narrative construction itself. His method was analogous, in a way, to that of novelists like Robbe-Grillet (e.g. 'Jealousy'), though Wyborny was far more interested in the actual materials of film than were the french 'new novelists' when they turned to cinema. His work was further characterised by a romantic appreciation for desolate, ruined vistas. The 1975 Pictures of The lost Word is clearly an outgrowth of this concern and, in its virtual abandonment of storyline, forms a bridge to his subsequent, more purely structural films.

For 50 minutes or so Pictures presents a series of static, or gently swaying images which are sometimes bucolic landscapes but more often industrial ones (sludgy harbours, power lines, abandoned railway stations or deserted factories). The interplay between the two sets of imagery is not simple. Wyborny photographs his modern ruins at their most ravishing - at dawn or sunset, partially reflected in the water or glimpsed through the trees. Shots recur throughout, optically printed into brilliant colours or else, given the washed out quality of fifth generation Xeroxes. As there are few people shown, one's impression is of a planet that is populated mainly by cows, barges and hydraulic drills.

On the soundtrack, a pianist improvises a slow, chord-heavy piece that adds to an overall sense of lush melancholy. Towards the end, Wyborny begins to parody his own nostalgia. The images repeat in rapid-fire clusters while the pianist switches to a maddening seven-note phrase, playing it over and over, like a record stuck in a groove. In its mock symphonic form, the film is an ironic exaltation of the ‘pastoral ideal' (still a strong strain in both British and German avant-garde films) as it celebrates the entropic beauty of the same satanic mills that drove Wordsworth in the countryside and Schiller to decry the 'degeneration' of European culture.' - J.Hoberman, The Village Voice, New York, May 1978.

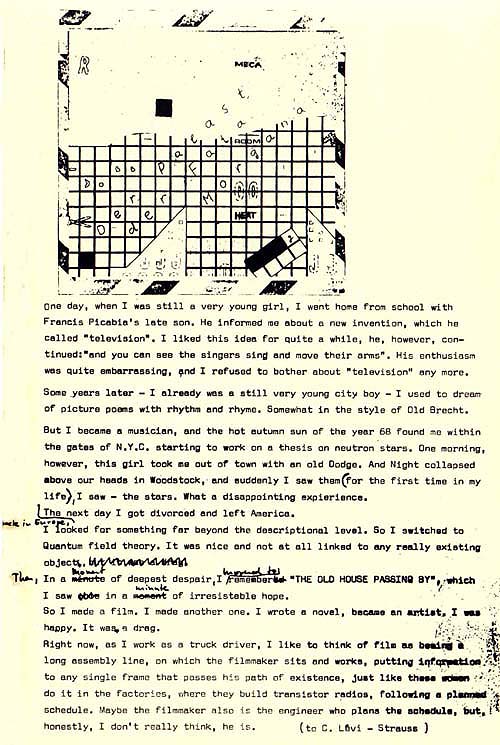

(temporal structure in high resolution)

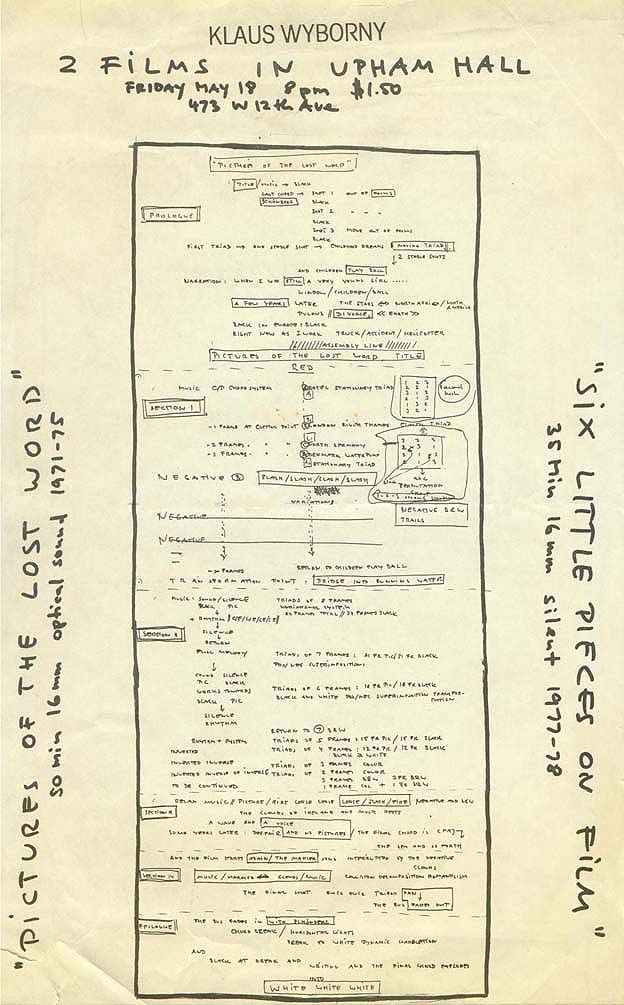

Programmankündigung mit Kompositionsschema - Announcement of a film-event with "Pictures Of the Lost Word"

Columbus/Ohio 18.5.79

K.Wyborny zur Arbeit an "Pictures of the Lost Word" und Strategien zu ihrer Verbesserung (aus Gespräch mit Klaus Wyborny - Die Grammatik der Welteroberung" - "Filmkritik" 10 / 79 - S. 464 ff.