K. Wyborny

Essayfilm - 103 Min 2014

Buch, Regie, Produktion, Kamera, Bildbearbeitung und Schnitt: K.Wyborny

Essayfilm in zwei Teilen - Essayfilm in two parts

I.

1. Théodore Géricault (1791-1824)

2. Claude Monet (1840-1926)

3. Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

4. Dieppe

5. Pourville sur mer

6. La Scie (1882)

7. Belle-Île 1886

8. Annäherung an Vater - approaching father (interview with Michael Snow)

II.

1. Nur einen Sommer

2. Pourville Revisited

3. Pourville Richtung / in the direction of Varengeville (1882 - 1897)

4. 1882

5. Ebbe / at low tide

6. Vom Kleinerwerden von Objekten und Menschen und ihrem Verschwinden - Of objects and people getting smaller, and of their disapperarance

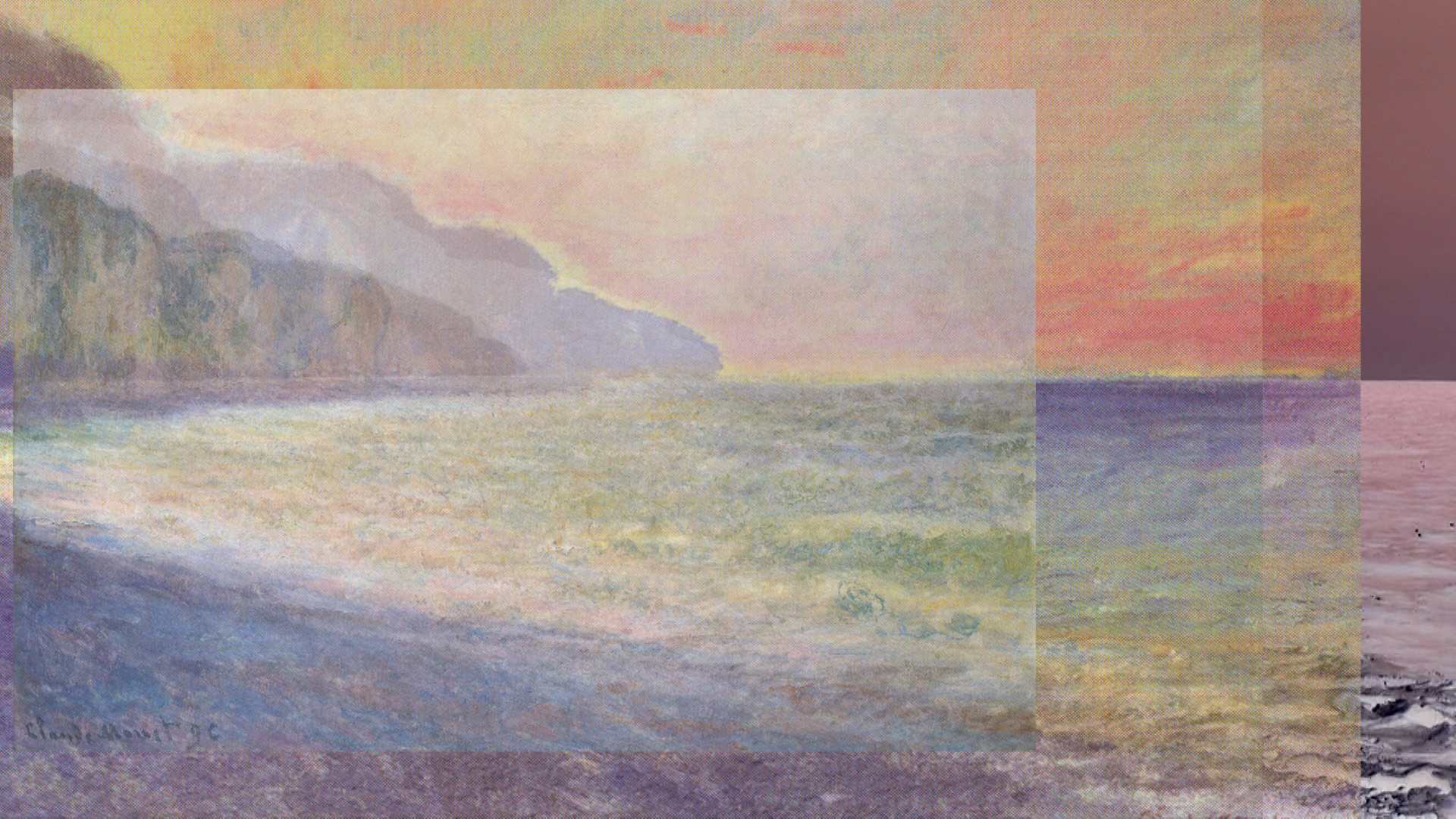

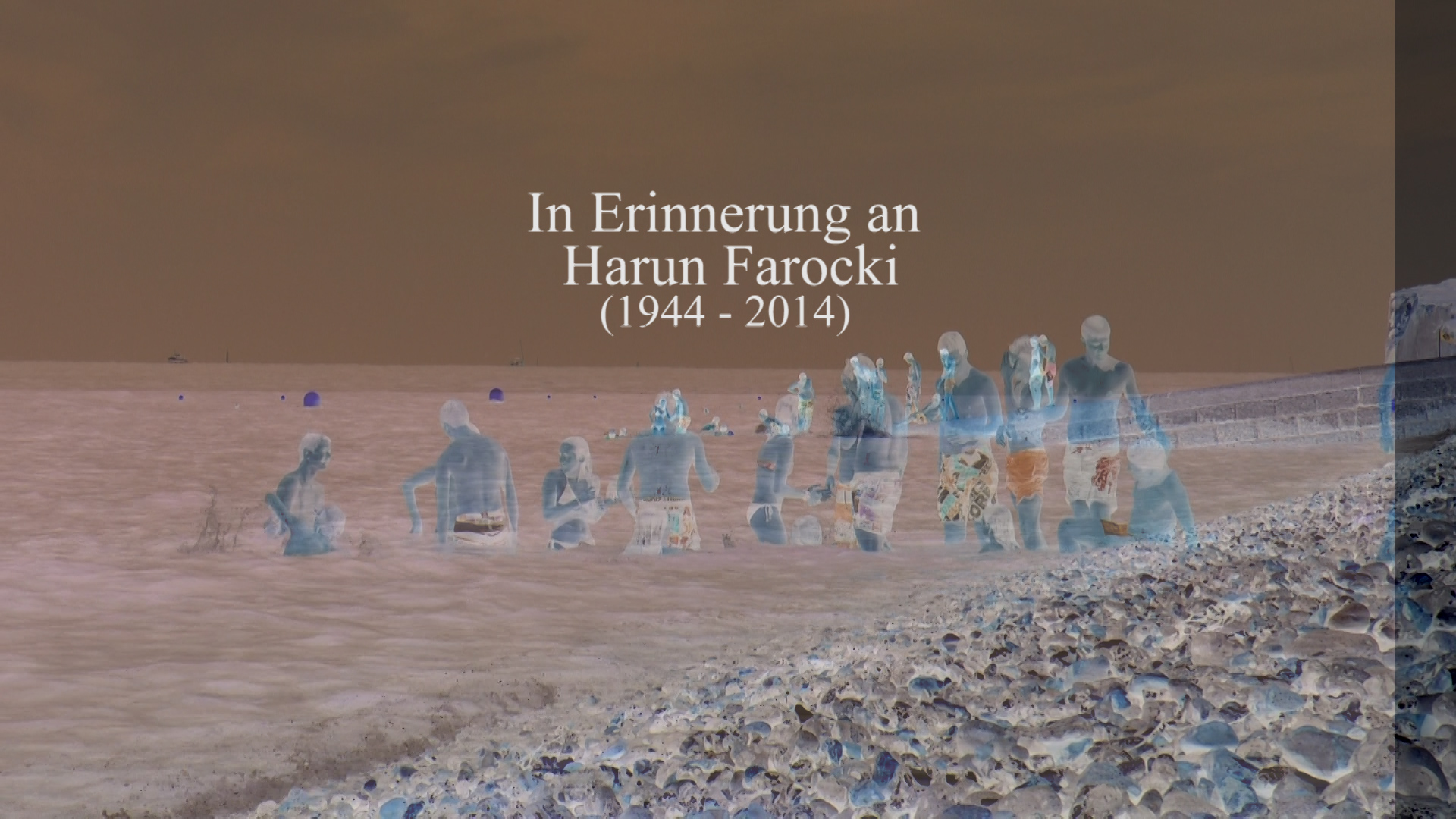

Etwa 140 Landschaftsbilder sind erhalten, die während vier längerer Aufenthalte Claude Monets zwischen 1882 und 1897 im normannischen Pourville enstanden. Nur wenig hat sich der wilde Küstenstreifen seither verändert, umso aufregender das durch die Geschichtsdimension bereicherte Präsenz-Panorama, das Wyborny in seinem, Harun Farocki gewidmeten, Essayfilm entwirft, indem er Monets Gemälde mit dem Filmbild der gegenwärtigen Wirklichkeit des Ortes überlagert. Eingeleitet von einem Interview mit Experimentalfilmer Michael Snow, dessen LA RÉGION CENTRALE nicht wenigen als Höhepunkt einer künstlerischen Auseinandersetzung mit Landschaft gilt.

There are about 140 landscapes painted by Claude Monet in Pourville during 4 long stays between 1882 and 1897. The coastline has hardly changed since then. Enriched by the historic dimension Wyborny presents a panorama of this coast by superimposing Monets paintings with the present reality of the location. His essayfilm is dedicated to Harun Farocki and includes an interview with Michael Snow whose "La région centrale" is considered to be a climax of artistic reflections on representing landscapes.

Klaus Wyborny’s neuestes Werk, der Essayfilm Studien zu Monet (aus dem imaginären Museum) setzt sich mit Monets Schaffen in den 1880er Jahren an der normannischen Küste auseinander. Der in zwei Teile gegliederte Film führt den Zuschauer zunächst auf eine kunstgeschichtliche Fährtenlese in ein Museum, in dem Wyborny durch seine Einstellungsanordnungen den großen Impressionisten Monet mit Théodore Géricault und Marcel Duchamp in Verbindung zu bringen sucht. Minutenlang entfalten sich deren Werke in flüssigen Kamerabewegungen und präsentieren sich ungestört von jeglichem Kommentar, scheinbar zum Zweck reiner Schaulust dem Zuschauer.

Auf diese Vorbereitung folgen im zweiten Teil Kamerasequenzen von Küstenabschnitten in der Normandie, wo Wyborny mit seiner eigentlichen Annäherung an die Werke Monets beginnt, indem er anfängt diese in seine Küstenaufnahmen einzufügen. Die Impressionen erscheinen mal wie fast durchsichtige Dias über dem Filmmaterial, dann wieder opaker, die gefilmte Wirklichkeit Wybornys verdrängend. Zeit und Raum beginnen sich in diesen gefilmten Reproduktionen der monet’schen Motive aufzulösen, Realitäten verschmelzen. Spaziergänger die durch die Aufnahme laufen wirken plötzlich, als würden sie die gemalte Wirklichkeit Monets betreten. Es sind aber nicht die Verschmelzungen zwischen Kamerarealität und Bildrealität, sondern gerade die Differenzen zwischen den beiden Medien Film und Malerei die dazu anregen, dass man beginnt Monets Kompositionen als Zuschauer selbstständig zu untersuchen und dessen suchendes Bemühen hinter seinen Bildern, die Intention seines Schaffensprozesses, und nicht die des fertigen Werkes, zu verstehen beginnt. Gerade die Fülle an Bildern, mit der Wyborny den Rezipienten im Laufe des Filmes konfrontiert, ist es, die das Wesentliche dieser Malerei, vor allem aber deren Wesen, enthüllt. Immer wieder unterbricht er diese Sequenzen, mit Einblendungen von Gedichten, eigenen Überlegungen und anderen Aufnahmen um künstlerische Gegenpole zu erschaffen, die zu neuen Ansichten über Monet führen. Anstatt dem Publikum seine Meinung über den Maler aufzudrängen schafft er durch seine essayistische Struktur vielmehr den nötigen Freiraum, sich selbst ein Bild von Monets Bildern machen zu können. Mit viel Feingefühl und Zurückhaltung ermöglicht der Regisseur dem Zuschauer damit eine sehr sehenswerte Annäherung an den Künstler und sein Werk, weit ab von der populärkitschigen Mainstreamaufbereitung vergangener Dokumentationen.

Maria Hunger

Vom Titel ausgehend „Studien zu Monet“ könnte man denken, dass Klaus Wyborny sich rein auf Monets Kunstwerke beziehen würde, was er auch fast tut, jedoch nur fast. Nebenbei lässt er den Zuschauer sowohl in Kunstgeschichte, wie auch in die Rubrik, Landschaftsfilm eintauchen, dazu später mehr. Zunächst zum Wesentlichen, was der Film, zumindest visuell, bietet. 103 Minuten lang bekommt der Zuschauer hauptsächlich Küsten und Klippen, meist aus Pourville, eine Region im Norden Frankreichs zu sehen, an welcher die Standorte aufgesucht werden, an denen Monet sich befunden haben musste, als er seine Bilder malte. Wyborny beweist seine forschende und filmische Genauigkeit und Monets malerische Präzision, indem er Monets Gemälde über seine Aufnahmen legt.

Die ersten Minuten des Films sind ein lehrender Einblick darüber mit welchen Künstlern sich hier Wyborny auseinandersetzt hat, damit im weiteren seine Handlungen und Effekte sich von selbst erklären sollten. Ich schreibe bewusst sollten, denn ich bin überzeugt, dass es trotz seiner kunsthistorischen Einleitung, ein enormes Kunstwissen voraussetzt, um alles Abgebildete, oder eher seine eingesetzten Effekte verstehen zu können.

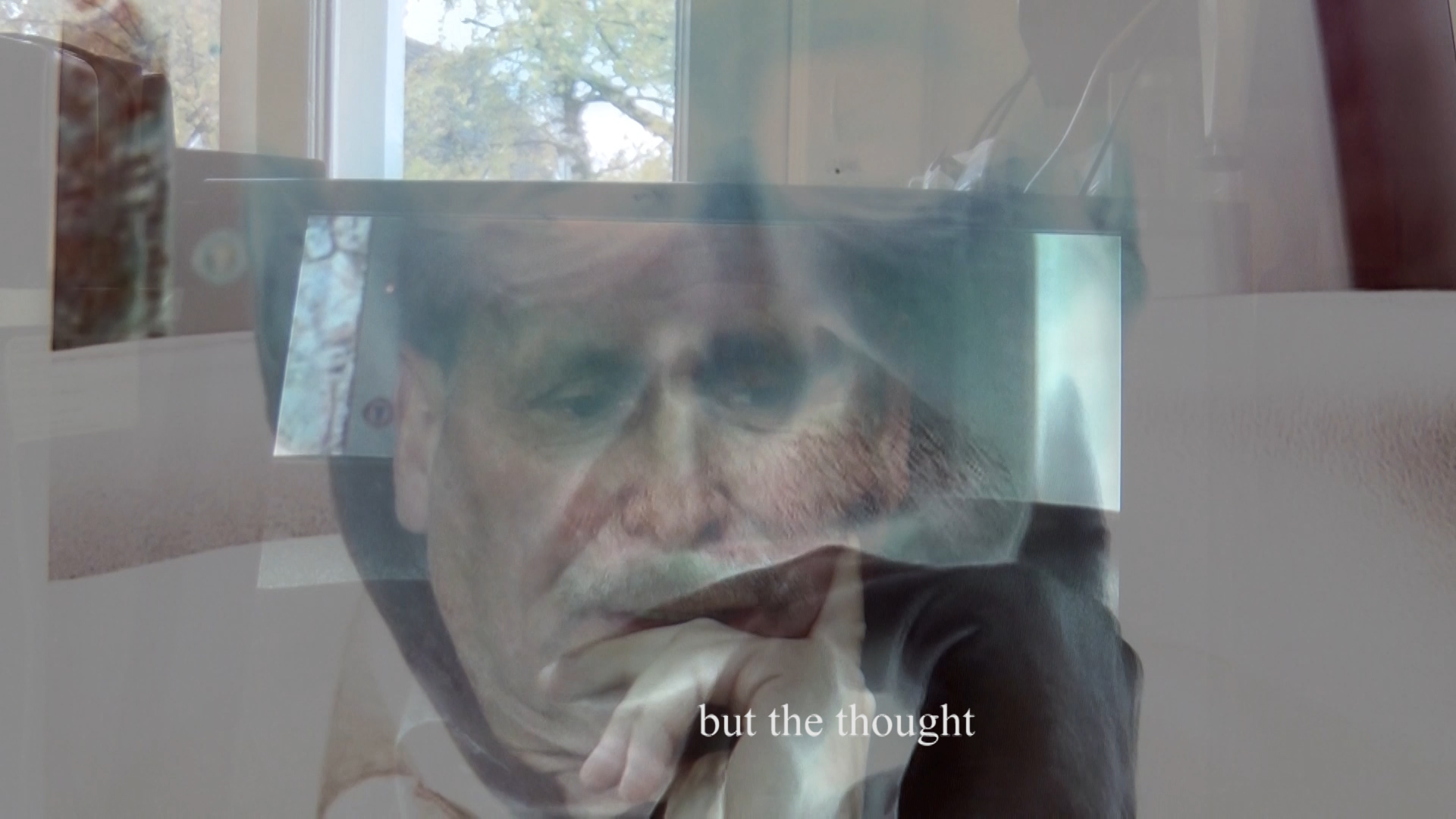

Der Beginn ist wortwörtlich ein Rundgang durchs Museum. Jede Aufnahme des gesamten Films ist mit Handkamera gefilmt. Wyborny zeigt chronologisch Bilder ausgewählter Künstler. Beginnend mit dem französischen Romantiker, Theodore Gericault, darauf folgt Claude Monet und dann geht es weiter zu Marcel Duchamp. Hierbei spielt Wyborny mit sehr einfachen Effekten. Er geht beispielsweise immer nur einen Schritt vor und zurück oder dreht die Kamera hin und her. Ab und an ertönt klassische Musik oder Wybornys Gemurmel. Ich könnte hier nun einen Versuch starten alles aufzuzählen, was Wyborny eingebaut hat und auf was alles der Film basiert, von Malerei bis hin zur Literatur und versuchen jedes einzelne Element, welches integriert wurde zu interpretieren, aber ich denke, dafür wäre weit aus mehr notwendig, als nur wenige geschriebene Zeilen. Da es nun nicht nur auf Kunsthistorik basiert, sondern auch auf Filmhistorik, möchte ich jenen Teil mehr hervorheben. Wybornys langjährige Auseinandersetzung mit Monet und seinen Standorten ist wie eine Art Landschaftsforschung, welche vom, für Landschaftsfilmer sehr einflussreichen und revolutionären Film, „La Regoin Centrale“ von Michael Snow, ausgeht und manche die von Wyborny eingesetzten Effekte auf jenem Film basieren. Wyborny widmet somit einen Teil, „Annäherung an Vater“, Michael Snow. Michael Snow schaffte 1971 einen Landschaftsfilm, welcher die Landschaft Quebecs auf den Kopf stellen lässt, indem er eine Kamera eingesetzt hat, welche eine 360° Drehung schaffte. „Annäherung an Vater“ wirkt zunächst wie ein Flashback, wie eine visuelle und auditive Irrfahrt. Alles läuft rückwärts und es ist, als wäre man in einem Gedankenstrom/-komplott, solange bis jene Szene auf einmal richtig abläuft, ohne Effekt und jener Moment zu einem eher langweiligen Smalltalk zwischen Michael Snow und Wyborny wird, welcher ihn mit seiner Handkamera stetig nur umkreist. Michael Snow scheint Herrn Wyborny Handwerk zu vertrauen, wirkt jedoch etwas verwirrt über Wybornys Herangehensweise ein Interview zu führen. Der Effekt der 360° Drehung begleitet den Zuschauer den ganzen Film lang. Einmal sind beispielsweise Kinder am Strand zu sehen, zuerst kopfüber, dann wieder richtig gedreht, bis beide ineinanderfließen, überdeckt mit einem Farbeffekt.

Ganz zum Schluss endet jene Studie mit einem Klippenstandbild, in welchem Wyborny seine Aufnahmen mit einer Arbeit von Duchamp,sowie einem kräftigem Pferd und einem Athleten, gemalt von Theodore Gericault, überlagert und diese Objekte wie bei einem Ballett herumtänzeln lässt. Jener letzte „Effekt“ erklärt den Beginn, also den Rundgang durch das Museum. Wyborny weist mit jenen eingesetzten Gemälden, sowohl auf die (Leb-) Zeit der Künstler hin, die Grenzen zwischen Natur und Malerei, wie auch auf die Schwierigkeit an diese Naturmotive heranzukommen.

„Studien zu Monet“ ist ein Film, welcher meiner Meinung nach zweigespalten ist. Einerseits bewundere ich Wybornys Ausdauer und Recherchearbeit, da er bereits seit 1998 an jenem Projekt gearbeitet hat, andererseits sind die von ihm besuchten Orte, Touristenorte, da viele zu jenen Orten pilgern wollen, an den Monet einst beim Malen seiner Motive gestanden hat. Genauso bewundere ich Wybornys Kunstwissen, welches auf jeden Fall Voraussetzung sein sollte, um seinen Film nur annähernd verstehen oder genießen zu können und wie bereits erwähnt, eine genaue Auseinandersetzung und Interpretation sicherlich Spannung garantiert. Einige eingesetzte Effekte lassen den Zuschauer auf jeden Fall für einen Moment aus dem Klippen-schauen-Koma erwachen, als Wyborny beispielsweise von ihm aufgenommene Reiter am Strand genial in ein Gemälde einfließen lässt. Leider gibt es eben nur wenige jener Momente. Wyborny spart mit Musikeinsätzen, umso mehr lässt er den Zuschauer sein Anstrengen hören, indem stetig sein schweres Atmen zu hören ist, was nicht immer störend wirkt, da seine Studien ihn auch zu schwer erreichbaren Plätzen führten und jene Anstrengung darf auch hörbar gemacht werden.

„Studien zu Monet“ ist auf jeden Fall eine Studie, die unvergessen bleibt, egal, ob als Natur-Kulissen-Schau kombiniert mit Geschichte der Kunst und des Landschaftsfilms, oder als Klippen-schau-Koma mit Atem-im-Genick-Effekt.

- TFM - Viennale 2014

Hello Klaus, Thank you for sending your beautiful videos. I did watch STUDIEN ZU MONET on the Friday that it screened in Vienna. I am overwhelmed at how thorough all your work is. So completely investigated. At first I was tempted to ascribe it to the video medium, but then remembered STUDIEN ZUM UNTERGANG DES ABENDLANDS which certainly has a film basis. In the case of

STUDIEN ZU MONET, I must say there were times that I thought you surpassed the old master. I particularly can't forget a view of churning surf which is pea green. If that shot were a painting, it would be world-famous. I envy your ability to travel to the beaches of Normandy. I went to Varengeville about ten years ago to visit the grave of my favorite composer, Albert Roussel - in the church yard overlooking the sea. The church also contains a George Braque stained glass which I also wanted to see. Your work beautifully

captures the feel of that coast. I appreciate your use of the term "studies". This so aptly describes the careful, attentive and, as I have noted, thorough contemplation of the subjects you address. And, indeed, we filmmakers of the present do need to find a way to engage with locations in a manner that can mirror the concentration and commitment of painters. I think your work does that. I include DAS LETZTE JAHR in these remarks. The observation of the yearly cycle is a strong link between many filmmakers and painters of the past.

.- Jerome

Dear Klaus--

The semester has finally ended and I can catch up on my email. Thanks for the lengthy response! Really appreciated gaining deeper understanding of your intentions and values.

you're welcome and i guess we both share the same filmic upbringing in many senses although yours started sooner than mine of course!thank you very very much for your kind words about my little Imaginary Museum. It's a great gift to see it through the eyes of a fellow artist, whose way of looking at film-things was also - i would almost say: bodily! - trained by the works of the avantgarde since the 70s.

that makes complete sense to me-- you being this generative artist that is about taking what you know/see/absorb/bodily understand and then using it in improvisatory ways to create films you discover in their making. so this beach scene is more your essence to me than the strictness of the structure and the art history lessons you are conveying. so for me the scene isn't a surprise or without purpose but a confirmation of your indomitable aesthetic spirit.Before I refer to Monet, I'd like to respond to two of your observations that immediately hit me. First your comments on the children's scene throwing pebbles into the sea, and that your boy liked it. Its also my favorite image, maybe because it doesn't really have a purpose and sits there just for itself. Whereas all the other shots clearly have an exploring undertone, meaning I wouldn`t have taken them without my occupation with Monet.

hadn't thought of Wavelength in relationship to this scene, thanks. will think about that on next viewing.But then, listen: To import it into the film, I had to put it upside down, turn it into color negative, doubleexpose it with the positive and generate a very slow zoom (in reference to Michael's Wavelength).

the friction between the demands of your structure and your ability to improvise and respond in the moment really brings the film to life! the Imaginary Museum is as you say via Duchamp, quite a restriction in terms of it's overall themes and requirements. but you being aesthetically who you are, are able to lift what would be for me unbearable didacticism in most filmmakers hands, into an exciting work in it's own right.So it had to be completely distorted, before it got presentable in a film context that satisfies our developed artistic sensibility. And that's in part Duchamp's legacy. After Duchamps even this delicate shot can only survive by extreme deformation.

So in a certain way, we have to look at whatever reality offers imagewise, through the peephole of Duchamps Philadelphia installation, the magic door, behind which some dubious pornography lures. Meaning in simple words: the whole world has turned, if you will, into a pornographic object. Or at least: there is a suscpicion luring that drifts into exactly that direction!

truly wonderful irony of your accomplishment that it transcends the virtual, and spins us back into the physical and the world of the senses. but this is a pretty daft and creative application of duchamp i suspect-- as uncanny and inspired as the beach scene.And so you won't be surprised when you hear, that the holes that mask some of the landscape shots in the film are the "original holes" of Duchamps door (Ha: actually they are only pictures of them, which is very interesting, because you "look through the picture of a hole", which is something no physicist ever dared to put his analytic brain into, but while you watch the film, it becomes unquestioned reality!).

yes i see. the Newton is a very "perfect" idealized body (which i very much doubt he possessed?) and lacks the flawed humanity of Gericault's athlete.So this is point one. Now point two, surprising me even more. It's your suspicion, that the Gericault's athlete is some kind of an imaginary self portrait. I haven't thought of it that way up to now. But now I can see a strong relation to William Blakes "Newton" (attached http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0e/Newton-WilliamBlake.jpg) which impressed me in the 70s. You see, I'm a trained physicist, but somehow I never could identify with the coolness of the Newton portrait. I think the Gericault is an improvement on the "Scientist", because Gericaults specimen is not so bloodless, but an athlete, and instead of the compass which he uses as an instrument, geometric objects lurk in the background. etc etc ...

i'll need to revisit with this new information and perspective. do you think part of what interested your friend Kippenberger is the flawed humanity in Gericault?now what is interesting is that in the film you can watch my fascination with this painting in statu nascendi. Because before I "filmed" the room I had hardly looked at the paintngs, i was just surprised, that there was a whole room with Gericaults (And Gericault was on my agenda because my friend Kippenberger busied himself with Gericault's "Raft of Medusa" in his last months). And as soon as I realized it, I turned on the camera and looked at the paintings through the viewer while the camera was recording. So you can notice the slight hesitations at the athlete, also when the camera records the way back.

yes i see what you mean about the stage or sense of proscenium in my work. this is derived from my fascination in general with the tableau and specifically with early film. i'm also enamored with the way tableau compositions gets taken up inside much 60's and 70's experimental film work, especially Warhols and also the structuralists too-- gehr and snow both come to mind.But even then "self portrait" would go too far. This changed when I was composing the last section of the film. In this I was strongly influenced by your films, by setting up the hole screen as some kind of a stage (and I think that's maybe not the essece, but certainly a dominating feature of what you do!), in the sections of which certain things happen. And soon the whole coast became such a stage, in which artistic concepts of depicting reality were fighting each other like alien war-machines and so forth and so forth.

i'll look forward to that.OK, enough for one letter. You'll get a second one in time.

you're welcome and i look forward to continuing our conversation.Up to then: thank you very very much again ---

Typee Film zeigt

*

K.Wyborny’s

*

Im Imaginären Museum (Studien zu Monet)

Au Musée Imaginaire Études sur Monet

*

Que pas un peintre n'ait été un paysagiste avant que le paysage se fut délivré des figures qu'il avait à grand'peine rapetissées, en dit long sur la soumission de l'artiste à la nature, sur la limite des réalismes et de l'abandon au sentiment... - André Malraux, Les voix du silence

Dass kein Maler Landschafter gewesen ist, ehe die Landschaft sich der Figuren, die vorher mit viel Mühe verkleinert worden war, entledigt hatte, sagt viel über die Abhängigkeit der Künstler von der Natur, über die Grenzen des Realismus und über die Hingabe an das reine Gefühl - André Malraux, Stimmen der Stille

The fact that not a single artist became a landscape painter, until, first, he had laboriously pruned away the figures from his landscapes

has much to tell us about the alleged subjection of the artist to nature, about the limitations of realism and about his devotion to pure feeling

*

ERSTER TEIL Adagio molto semplice e cantabile

part 1

1. Théodore Géricault (1791-1824)

*

A sculpture by Géricault

*

2. Claude Monet (1840-1926)

*

Rouen 1892

*

3. Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

*

Oh, I didn't know that it is transparent ...

*

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

*

Dieppe

*

Pourville, vue depuis Dieppe

Pourville seen from Dieppe

*

Varengeville

*

La grande digue

Die große Mole von Dieppe

*

Pourville sur mer

*

La Scie

*

diverse Möglichkeiten

quite a few possibilities

*

Belle-Île 1886 (4 ans après)

4 years later

*

In Belle-Île malte Monet in 10 Wochen etwa 40 Bilder, bei denen, außer der Malweise, an seinen Motiven noch heute die Ausschnittwahl frappiert

In Belle-Île Monet painted about 40 landscapes within 10 weeks. In most of them the framing of his motifs is highly surprising.

Wie heißt diese Nummer? - 1113

What's this numner called? - 1113

*

1113 - Das Bild muss etwas quadratischer sein

1113 … The image must be a bit more quadratic

4. Annäherung an Vater

- approaching father –

*

La région centrale

*

vers père

*

père-vers

*

pervers / revers

*

What Klaus is doing right now refers to my film "La région centrale" in which the camera moves in circular movements.

*

- Where did you shoot this film anyway?

- Where? ... In Northern Quebec.

*

- And how far was it from civilization?

- The nearest town is called Sept-Îles which was a hundred kilometers away.

*

- And how much equipment did you bring to the place?

- A lot because we had the machine by which the camera was moved.

*

- And the preparation for this machine ... I was amazed ... there was a music tape controlling it?

- No ... That was something we tried to do, but it didn't work.

*

- Well, that was very early. It was 68 or 69?

- No, it wasn't possible to spend the time with respect to that. It was all done with dials.

- Dials?

*

- For three possible movements: horizontal, vertical, and zoom, and control of speed. So I made a kind of score which I tried to follow which would say:

Move vertically at the speed of two, with horizontal speed of three.

*

- And how many people were present?

- For the shooting Pierre Abaloos, who built the machine, and I were the crew.

*

„I want to make a gigantic landscape film equal in terms of film to the great landscape paintings of Cézanne, Poussin, Corot, Monet and Matisse...“ - Michael Snow 1969 in a proposal to the Canadian Film Board

*

- I love it if you don't mind ...

- Well, you are a very good filmmaker ... I trust that you will convert me into something interesting.

*

- I was busy filming Greek statues last year going around them, and now it’s wonderful to have a live statue. I can apply now everything I learned then. And we are both not young, but we are in much better shape than those Greek statues. They lost arms and tits and legs and all that kind of stuff, and we can still think and move.

*

This was always interesting, the face, going around it ... hesitating ...- Is this still OK with you?

- Yeah, I'd like to talk with you some more...

- Hm, I don't know, three minutes, ten minutes, five minutes? The battery is…

- Absolutely, but I'm kind of anxious to eat. - The battery would last three hours ... - OK, so I make some final things.

*

- Well, "La région centrale" is definitely one of the best movies that was ever made.

- Thank you ... When you say that I believe that there's something to it ...

- Yes, you can certainly believe it. There are no hindthoughts ... and things like that ....

Teil 2 Scherzo: Assai vivace ed appassionato (mit der innigsten Empfindung)

part 2 - with innermost sensibility //feeling//

Nur einen Sommer ...

Only one summer

*

Hölderlin's well known poem "An die Parzen" begins like this:

Nur einen Sommer gönnt, ihr Gewaltigen!

Und einen Herbst zu reifem Gesange mir,

Dass williger das Herz, vom süßen

Spiele gesättiget, dann mir sterbe.

Grant me only one summer, all powerful ones!

And an autumn for my song's harvest

that my heart more willingly, stilled by sweet

play, die to me.

*

The basic thought is simple: I greedily want a summer and an autumn

but the thought that my heart might die more willingly is highly complex:

"more willingly" almost means "unwillingly"

*

/// The following analysis of Hölderlins's unusual German syntax is not reproducable by English subtitles ///

*

-… that's well expressed by

that my heart ... more willingly die to me

*

And then the great dream of art that my heart, stilled by sweet play ...

So he wants to believe that there exists such a "stilled state", in which one accepts that one's heart stops beating.-

*

The state of having been stilled is our first sensation of happiness

when we suck on our mother's breast and our hunger is stilled

*

vers mère

towards mother

*

It's a state without greed, in which life is somehow absent.

Only when hunger starts life proper is beginning again.

*

So whatever you think of this poem

*

mer-vers (meerwärts)

towards the sea

*

it expresses something about the metaphysical substance of life

with a precision that cuts deeply into your heart

***

Pourville Revisited ...

*

Marcel Duchamp

gegeben / given / étant donnés

(1946 - 1968)

*

Varengeville sur mer

*

Hier liegt Georges Braque begraben ...

Georges Braque lies buried here

*

795 - a little bit closer

*

Die Wand

The Wall

*

Es geht nur am Rand darum, die Wirklichkeit naturgetreu abzubilden, eher geht es darum, etwas aus ihr hervor zu zerren, das einen weiterbringt und - vielleicht! - einer neuen Wirklichkeit Ausdruck verschaffen könnte ...

It's only part of one's task to depict reality true to nature. More essential is to pull something out of it, which carries you further and might give expression to a new reality.

*

Continental plate

*

Oliver Assayas shooting a commercial for L'Oréal

*

130 Jahre zuvor (1882)

130 years before

*

Von fremden Ländern und Menschen

Of Foreign Lands and People

Die weiße Wand

---- ein illuminierendes Gas ...

The white wall - an illuminating gas

***

5. Pourville Richtung Varengeville (1882 - 1897)

Pourville in the direction of Varengeville

*

Küstenabbruch 2012

cliff erosion / chute de pierres

*

Küstenverlauf vor 2012

the coast before / la côte avant 2012

*

gegeben:

1° Der Wasserfall

2° Das illuminierende Gas

given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas

*

- Oh, I have seen a flash

*

Zwar liebte er die Natur mehr als das Museum, seine Bilder liebte er jedoch mehr als die Natur ...

He loved nature more than the museum, but his paintings he loved more than nature ...

***

Ebbe

at low tide - à marée basse

*

Horizont genau in der Mitte, und ein bisschen nach rechts

Horizon right in the middle, and a bit to the right

***

Vom Kleinerwerden von Menschen und Objekten

Of men and objects getting smaller

*

und ihrem Verschwinden ...

and of their disappearance ...

*

Jede Epoche ist für sich selbst Gegenwart: jede stirbt im Wochenbett, ohne das Kind, das wir kennen, gesehen zu haben.

Each epoch has presence in itself; each one dies giving birth, without seeing the child that we know.

*

Zwar zeigt uns die Natur mit unmissverständlicher Gewalt, was natürlich ist; gleichwohl revoltiert unser Geist gegen diese Natur

Nature shows us with force what is "natural", but our mind revolts against this nature

*

Aber die Wüste, sie wächst!

But the desert is growing

*

Drum auf, Franzosen, eine letzte Anstrengung!

Let's go, Frenchmen, one last effort!

*

-Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses ...

Seid der Liebe zugeneigt und ihr werdet glücklich sein

*

In Erinnerung an Harun Farocki (1944 - 2014)

In memory of Harun Farocki

***

Great artists +

*

(eingemeißelt in Stein)

(chiseled into stone / cisilé en pierre)

*

the most beautiful music on earth ...

*

Aus dem Imaginären Museum (Studien zu Monet)

Études sur Monet - Dans le Musée Imaginaire

/// vorläufige Fassung (B3) vom 20.9. 2014 ///

*

Mit Michael Snow (Berlin 2012)

*

Produktion Regie Buch Kamera Bildbearbeitung und Schnitt K. Wyborny

*

Dank an Norbert Arns und Corinna Belz für ihre Aufnahmen aus Philadelphia

Elfie Mikesch und Harald Bergmann für die Aufnahmen (2002) zu "An die Parzen"

Laurence Rickels für seine Übersetzungen

*

Assistenz A. Willig-Wyborny

*

Die Nummerierung der Bilder Monets folgt dem Catalogue raisonné von Daniel Wildenstein

*

Dank an Lewis Klahr, Morgan Fisher, Thom Andersen, Ken Jacobs, Jerome Hiler, Ben Russell, Heinz Emigholz, Rudolf Thome, Olaf Möller, Durs Grünbein, Martin Aust, Ron Green, Christopher Zimmermann, Federico Rossin, Alexandre Estrela, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Peter Hoffmann, Thomas Friedrich und Hans Hurch

*

© copyright 2014 K. Wyborny

© copyright K. Wyborny 2014 - 2015

zurück zur Filmographie / back to the filmography

zurück zum Hauptmenue / back to main menue